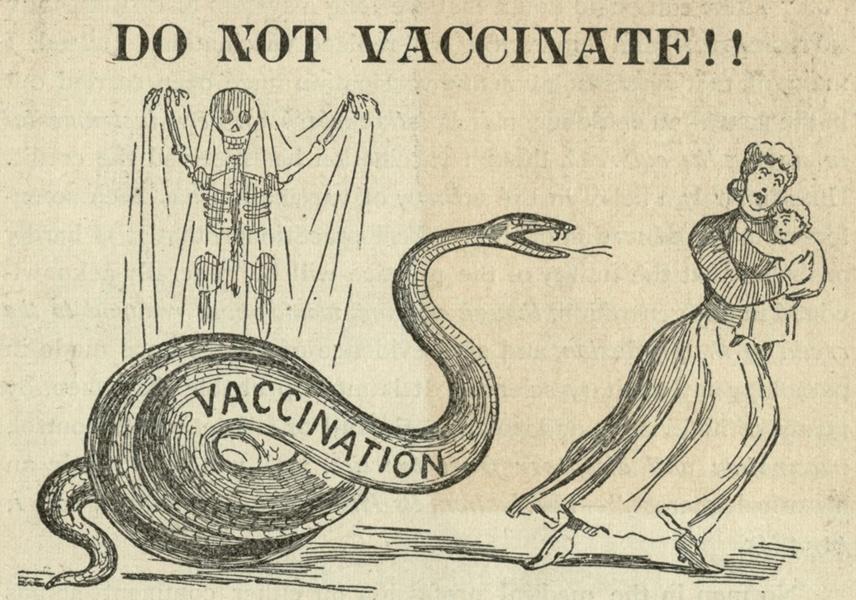

Feature image credit: Cartoon from an 1892 anti-vaccination publication (Historical Medical Library, College of Physicians of Philadelphia).

This story was originally published in the Peterborough Local History Society magazine (Volume 64, April 2025).

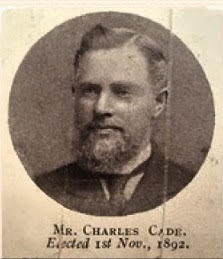

In the previous issue, I shared the story of C.E. Wood, who was exposed as a fraudulent spiritual medium in 1882.1 Present at the séance that evening were Robert Catling, the host, Thomas McKinney, a prominent local Spiritualist, and Charles Cade, the man who snatched Wood. While working on that story, I kept happening upon these men’s names in an entirely different context. From 1884 to 1888, all three were vocal critics of vaccination, with two of them being prosecuted under the Vaccination Act for refusing to have their children vaccinated against smallpox. They were not alone. Vaccination was controversial from the beginning, but in the 1880s an anti-vaccination movement emerged which has only since been rivalled by that of recent years.

It is easy to forget the extent to which vaccination has transformed our world. Diseases like plague and polio ravaged populations for thousands of years but are now either extremely rare or extinct in their wild form. One of the most feared diseases of all time was smallpox. Smallpox first emerged between 3,000 and 4,000 years ago2 and has even been found in Egyptian mummies. In the 20th century alone, it is estimated to have killed 300 million people.3 Today, it only exists in laboratory samples. Debate continues about whether these too should be destroyed.

It was smallpox which led to the first modern vaccine in 1796. Most will be aware of Edward Jenner’s discovery that people with the relatively mild cowpox were thenceforth inoculated against the much more deadly disease. In fact, this is the origin of the word, from the Latin vacca, meaning cow.

In the 19th century, the British government passed a series of laws to ensure that vaccines were administered nationwide. The Vaccination Act of 1840 offered free vaccination to the public and outlawed variolation, the previous technique where infected material was rubbed directly into scratches in the skin. The 1853 act would prove to be the most consequential. It dictated that every child under the age of three months (four months in the case of orphanages) had to be vaccinated. If parents failed to notify registrars of their child’s vaccination, and failed to give sufficient reason, they had to pay a fine of £1. Further acts in 1867, 1871, and 1874 served to strengthen the law.

Opposition to vaccination came from various quarters, not least because epidemics were still poorly understood. The germ theory of disease only began to hold sway in the 1880s after centuries of uphill struggle, and many scientists still promoted miasma theory. Even the people promoting vaccination did not understand how it worked, only that it was empirically effective. There were also genuine risks, including accidental infection from diseases like scrofula and syphilis as lymph came directly from other people, later to be replaced by calf lymph.

In addition to these scientific objections, religious clerics criticised the idea of mankind interfering with divine providence. Others said that the legislation infringed upon civil liberties, which was undoubtedly true, even if justified from a public health perspective.4 19th-century vaccination was quite different from that of today as flesh had to be gouged out of children’s arms multiple times. Parents asked how the government could force such a traumatic procedure on their children and usurp their parental rights.

One man from Broughton Clays in Lincolnshire described how many parents felt when ordered to vaccinate their children: ‘John Pinder, of Broughton Clays, was charged with neglecting to have his child vaccinated. Defendant said he did not agree with vaccination. His children were pure and healthy, and he wished to keep them so. He would not put impurities into their blood. Fined £1 and 10s. 6d. costs.’5

At first, the Vaccination Acts were poorly enforced, but this changed after a smallpox outbreak that spread across Europe from 1871. The 1870s saw the largest number of deaths for the whole century.6 People who thought they had escaped the laws’ reach now received fines for non-compliance. With this, the anti-vaccination movement exploded in popularity. In 1885, an estimated 100,000 people attended an anti-vaccination protest in Leicester, almost equalling the population of the city itself as people flocked from around the country.7

Of the men who were present at Peterborough’s infamous 1882 séance, at least three became pronounced anti-vaccinationists. This is not surprising as Spiritualists were some of vaccination’s most prominent critics. Dorothy and Roy Porter even point to this as a source of division in the movement: ‘Its northern, working-class advocates were not readily persuaded by southern, middle-class intellectuals with their advocacy of “natural healing” and spiritualism.’8

In 1884, Thomas McKinney took part in an anti-vaccination demonstration in Peterborough. Protesters brought banners saying, ‘They that are well need no physician,’ ‘£200,000 spent annually in vaccination fees,’ and ‘Down with Medical Despotism.’ The Peterborough Standard gave them short shrift, saying, ‘On the front of the wagon were two flaming placards, accusing some one or the other of murder. By the majority of those present the proceedings were looked upon in the light of a joke.’9 The article ends by saying, ‘It is proposed to start an Anti-vaccination League in Peterborough, but, from the small amount of enthusiasm manifested on Tuesday and Wednesday, it does not promise to be a great success.’

Curiously, McKinney wrote to the Peterborough Standard in 1886, quoting evidence from the London Smallpox Hospital that seemed to support vaccination’s effectiveness.10 William Tebb wrote a response to that letter which cast doubt on the results.11 McKinney had opposed vaccination for at least two years at that point and was described as a ‘well-known anti-vaccinationist’ in 1888.12 We cannot be sure of McKinney’s intentions, but perhaps this was a way to have Tebb, a Londoner, featured in the local press.

A fellow Spiritualist, Tebb was perhaps the most prominent anti-vaccinationist in the country. He founded the London Society for the Abolition of Compulsory Vaccination in 1880 and later testified before the Royal Commission alongside Charles Creighton and Alfred Russel Wallace in attempts to have the laws repealed. The Society advertised in publications we know were read by Spiritualists in Peterborough.13

The Peterborough Debating Society held a meeting in 1887 debating the motion that no change in the vaccination laws was desirable. McKinney spoke against this, saying, ‘that when he said that compulsory vaccination ought to be abolished he believed he was expressing the opinion of the majority of the people of the country. He objected to vaccination because it was an evil law unfairly administered. It had been proved, he remarked, that the system was a source of disease and death to many subjects of this country, and he quoted statistics of mortality in proof of this assertion. The doctors themselves were beginning to disbelieve in the efficiency of vaccination as a preventative against small-pox, and this, he observed, was a significant fact, which showed that the people were right, and the doctors wrong.’14

In 1887, Robert Catling was fined £1 for not having his child vaccinated.15 These fines were controversial, not least because they could be administered repeatedly for the same offence. Where people could not pay, their belongings could be confiscated and auctioned off in distraint, or distress, sales.16 Charles Cade refused to have two of his children vaccinated, leading to an increased fine the second time. This would lead to dramatic scenes when he refused to pay.

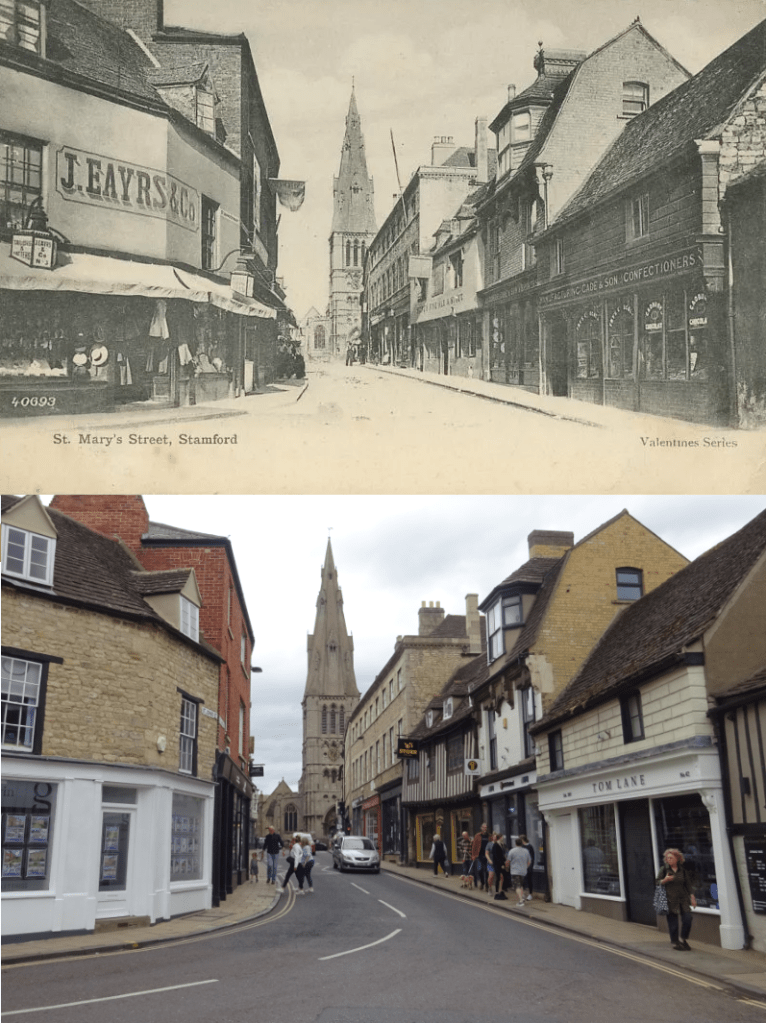

Charles Cade was a confectioner and auctioneer with premises at 41 and 42 St. Mary’s Street in Stamford. Remarkably, we still have his recipe for raspberry treacle, which he patented in 1884.17 That same year, Cade spoke in defence of Annie Besant when her invitation to speak at Oddfellows Hall was rescinded due to the ‘mischief’ she might cause.18 At that time, Besant was a leading exponent of secularism, socialism, and feminism, later becoming president of the Theosophical Society and the first female president of the Indian National Congress who fought for Home Rule.

On 11th June 1884, Cade was ordered by Magistrates to have his daughter Amy vaccinated within 21 days. He refused and was called before the Stamford Petty Sessions on 27th September. He had already been fined for another of his children but was surprised when the fine this time was increased from 6d. to 10s.:

‘Mr. English (the Magistrate’s clerk): Do you admit the order?

‘Mr. Cade: Yes, the child has not been vaccinated; you know the reasons.

‘Mr. English: You have not been summoned before in respect to this child, have you?

‘Defendant: No.

‘Mr. Michelson: You will be fined 10s. and costs.

‘Defendant: Your Worships, in the last case you only fined me 6d.; That was a first offence, same as this.

‘Mr. Morgan: You are putting the law at defiance; you will not have your child vaccinated.

‘Defendant: You do not suppose a 10s. or a £10 fine will make any difference? Seeing that Dr. Morgan is here, I will tell you of a singular thing. He made light of what I said about drainage the last time I was before the Bench. The week following he was called to one of his own brethren who was at death’s door through the drainage!

‘Mr. Michelson: We are not arguing whether vaccination is right or wrong: you must obey the law or take the consequences.

‘Defendant: You have power to carry out the law leniently.

‘Mr. Michelson: That is leniently; we might fine you £3.

‘Defendant: It has been your custom to fine us 6d. lately.

‘Mr. Michelson: But you take no notice of that.

‘Defendant: Then I shall have to allow you the unpleasant duty to distrain for it. I shall not pay it.’19

Anti-vaccinationists soon came to Cade’s defence. William Tebb wrote to the Peterborough Standard to support him and attack ‘Jenner’s partizans.’20 When police came to enforce the distraint, seizing a harmonium and selling it at auction, the public came out in force to jeer at the proceedings:

‘On Friday afternoon a very uproarious and exciting scene was witnessed in the Market-place at Stamford. A few weeks since Mr. Charles Cade, confectioner, a well-known anti-vaccinator, was ordered to pay a fine and costs for refusing to have his child vaccinated, and as he declined to pay the amount the police seized a harmonium of his, and on Friday afternoon it was taken to the Market-place, and submitted to public competition by a local auctioneer. Upon the auctioneer mounting the rostrum the crowd, numbering quite 500 persons, hissed and hooted and cheered by turns, and it was fully ten minutes before the sale could proceed. Eventually a start was made, and after a few bids the instrument was knocked down for £3 10s. amid the derisive cheers and shouts of the spectators, who by this time numbered nearly 1,000. There were six policemen on the spot. Addresses were subsequently delivered against the practice of vaccination. Several anti-vaccinators were summoned before the magistrates on the following day.’21

This was a significant crowd. According to the 1881 census, Stamford’s population was only 7,604 at the time. It is possible that, as with the Leicester protest of the following year, people were bussed in from other locations to show support.

Cade took issue with the way the distraint had been carried out, accusing the police of removing the harmonium illegally. It couldn’t have helped that the person who eventually made the purchase was an associate of one of the police officers:

‘A County Court summons has been issued against the Chief Superintendent of the Stamford police force, at the suit of Mr. Charles Cade, confectioner, who claims damages for an alleged illegal removal of a harmonium under a distress made under warrant issued by the borough justices. The Watch Committee have resolved the action shall be defended, and they have instructed the Town Clerk (Mr. Atter) to act as solicitor for the defendant.’22

Ironically, Cade would come to work with J.E. Atter when he joined Stamford Town Council a few years later. It is not known if they had a pre-existing relationship. Alderman Paradise asked Atter about the proceedings at a council meeting in January 1885:

‘Ald. Paradise inquired on the reading of the minutes if anything more had been heard of the action by Mr. Cade against the Superintendent of Police with regard to the recent vaccination proceedings. The Town Clerk replied that the sum of 5s. had been paid into court; that he did not think the action would go on; and that if it did he did not fear the result.’23

The case was heard on 21st January, with Cade making his own case. At times, the proceedings descended into laughter:

‘CADE (Chas.) v. WARD (Rd.)–Claim £3-10s. for the loss of use of a harmonium for a fortnight and £2 10s. loss sustained by illegal removal…

‘Mr. Cade, who took a position at the solicitors’ table, said, without being sworn: Shortly before the cause of this action I was summoned before the Borough Magistrates and convicted of refusing to obey an order of the Magistrates to have my child Amy vaccinated, and they fined me 10s. and costs; and because for a considerable time it had been the custom of the Magistrates to fine only 6d. for a similar offence I felt justified in refusing to pay…

‘THE JUDGE: You see the Magistrates gave you a fine of 10s. because you had been fined before.—MR. CADE: Not for that child.—THE JUDGE: I see what they meant: you by the previous conviction had been warned before.—Mr. Cade: I allowed the law to take its course, and warrants were applied for and a warrant of distress was issued against me and executed by constable Lightfoot and sergt. Palmer, who by my consent seized a harmonium. I contend that the harmonium was illegally removed from my premises. On the 14th November notice was brought to me that the harmonium would be sold on the Market-hill by auction that afternoon at 2 o’clock. I submit that the sale was an illegal sale under the Act.—THE JUDGE: The clear time (the five days) had elapsed.—Mr. Cade: The sale was not a public auction. It had not been advertised in any newspaper [it had been announced by the town crier].—P.c. Lightfoot was called by plaintiff, and said: I was with sergeant Palmer charged with a warrant to execute on plaintiff on Nov. 1. In carrying out the execution I entered the living room and with plaintiff’s consent seized the harmonium. Mrs. Cade said, “If I knew you were coming for it I would have had it cleaned ready.” Cross-examined by Mr. Atter: Plaintiff is a man well to do, keeping a large shop. I heard sergt. Palmer several times say, “You had better pay and not give us any trouble.” Plaintiff said he would not pay one farthing…

‘Mr. Cade favoured us with a lecture condemning the Vaccination laws. Mr. Cade harangued the people, and the auctioneer was intimidated. Everything was done that reasonably could be to sell the harmonium to the best advantage…

‘[Mr. Atton:] 500 or 600 people were present. Mr. Cade instead of helping me was reading the law behind my back. (Laughter.) They said I dare not sell it. I would not be a coward, and I sold it. The persons were hustling and yelling for Mr. Cade. It was quite a pantomime…

‘THE JUDGE (to plaintiff): You ought to have bought it yourself. I cannot make out why you did not… The police acted with consideration. By your conduct and by your wife’s’ conduct they thought they were entitled to remove the instrument.—Plaintiff: They might as well have come into my larder and helped themselves to my food…

‘Judgment for defendant; but no costs against plaintiff.’24

As far as I can tell, this is the last reference to Cade’s anti-vaccination activism. Amy was the last of his three children, so perhaps the issue never came up again. Cade seems to have moved from one popular movement to another, many of them exemplifying the times in which he lived. His enthusiasm is admirable, even if some of it seems misguided in hindsight.

It is unsurprising then that Cade would turn to politics. In 1891, he twice ran for Stamford Town Council on behalf of the Liberals. In 1892, he finally succeeded with 155 votes and became a councillor for St. Mary’s Ward.25 In 1901, he became the town’s treasurer, a role he seems to have retained until his death.

In 1909, Cade passed away on the premises of his shop at 42 St. Mary’s Street at the age of 59. He was commemorated by the Stamford Institution, of which he had been a leading member for 21 years.26 The following obituary gives some idea of his varied career:

‘On Thursday morning there passed away after a long and painful illness Mr. Charles Cade at the age of 59. Born at Northborough, he left there at the age of 15 and went to Peterborough, where he learnt the trade of a baker. After several changes of occupation he eventually settled at Stamford, where he started in business as a manufacturing and retail confectioner. Adding the business of auctioneer and furniture dealer he became a well-known man in the district. He entered the Town Council in 1892 as a Liberal and took an active and outspoken part in its deliberations. He leaves a widow, one son, and two daughters.’27

After Charles’ death, his son Alfred ran to fill his seat at the council and won with no challengers.28

The Leicester demonstration of 1885 probably marked the peak of anti-vaccination activism during this period, but debate continued for many years. Smallpox had been on the wane since 1871, other outbreaks being much more localised due to isolation and stronger controls at ports, so in 1898 a conscience clause was added to the law, meaning that those who applied for a certificate would be exempt from punishment.29

Now that smallpox has been completely eradicated, it is easy to judge those who opposed vaccination in the 19th century, but it is important to remember that the scientific debate was still raging and there were genuine risks associated with it. Thankfully, things have changed a great deal since then, even if people’s fears remain.

Special thanks go to the following people for helping with my research: Jane Craig-Tyler, Keith Hansell, Karen Meadows, Gail Mitchell (British Library, Business & IP Centre), and Stamford & District Local History Society.

- Tony Conn, ‘C.E. Wood: A Fraudulent Medium Exposed’, Peterborough Local History Society, vol. 63, October 2024, p. 22-33 [C.E. Wood: A Fraudulent Medium Exposed – Eccentric Orbits: Collected Writings from Tony Conn] ↩︎

- Catherine Thèves, Eric Crubézy, and Philippe Biagini, ‘History of Smallpox and Its Spread in Human Populations’, Microbiology Spectrum, vol. 4, no. 4, 1st July 2016, https://journals.asm.org/doi/10.1128/microbiolspec.poh-0004-2014 ↩︎

- Donald A. Henderson, ‘The eradication of smallpox – An overview of the past, present, and future’, Vaccine, vol. 29, suppl. 4, 30th December 2011, p. D7-D9 ↩︎

- For a good overview of the anti-vaccination movement, see: Dorothy Porter and Roy Porter, ‘The Politics of Prevention: Anti-Vaccinationism and Public Health in Nineteenth-Century England’, Medical History, vol. 32 (1988), 231-252. Nadja Durbach’s book, Bodily Matters: The Anti-Vaccination Movement in England, 1853-1907 (2005, Duke University Press), contains a wealth of information but has been criticised for inadequately addressing the smallpox vaccine’s efficacy: Michael Fitzpatrick, ‘The Anti-Vaccination Movement in England, 1853-1907’, Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, vol. 98, no. 8 (2005), p. 384-385. ↩︎

- ‘Newark County Police, Jan. 28’, Stamford Mercury, 30th January 1885, p. 5. For the sake of legibility and consistency, where newspapers have listed pounds as ‘l,’ I have changed this to ‘£.’ ↩︎

- Olga Krylova and David J.D. Earn, ‘Patterns of smallpox mortality in London, England, over three centuries’, PLoS Biology, vol. 18, no. 12 (2020), p. 1-27 ↩︎

- For a full account of the Leicester protest, see ‘The Great Leicester Demonstration’ from J.T. Biggs – Leicester: Sanitation versus Vaccination (1912, National Anti-Vaccination League), p. 107-130. ↩︎

- Porter and Porter, p. 235 ↩︎

- ‘Struck Out’, Peterborough Standard, 15th September 1888, p. 6 ↩︎

- Thomas McKinney, ‘Vaccination’, Peterborough Standard, 24th July 1886, p. 3 ↩︎

- William Tebb, ‘Vaccination’, Peterborough Standard, 7th August 1886, p. 3 ↩︎

- ‘Peterborough Debating Society’, Peterborough Standard, 15th January 1887, p. 6 ↩︎

- For example, The Medium and Daybreak, vol. 13, no. 649, 8th September 1882, p. 573. A letter in the following issue advised people to have their children vaccinated but to counteract the effects with a course of sulphur: William Young, ‘Is sulphur an antidote to the vaccine virus?’, The Medium and Daybreak, vol. 13, no. 650, 15th September 1882, p. 582. ↩︎

- ‘Anti-vaccination Meetings’, Peterborough Standard, 28th June 1884, p. 8 ↩︎

- ‘Peterborough Petty Sessions’, Stamford Mercury, 25th February 1887, p. 4 ↩︎

- Durbach, p. 52-53 ↩︎

- ‘No. 7013 – Specification of Charles Cade: An Improved Raspberry Treacle’, 15th September 1884 ↩︎

- Besant was supposed to deliver three speeches in Stamford that February but was forced to postpone until May. In the meantime, objections were raised about the mischief she might cause and her invitation was revoked. Cade spoke at a meeting organised by dissenters, saying that she was being persecuted for holding true to her convictions and that this was a matter of free speech. He was censured for suggesting the Oddfellows’ committee not be allowed to make decisions about what happened in its own premises: Stamford Mercury, 22nd February 1884, p. 4; Stamford Mercury, 21st March 1884, p. 6; Northampton Mercury, 22nd March 1884, p. 1. ↩︎

- ‘Stamford Petty Sessions, Sept. 27’, Stamford Mercury, 3rd October 1884, p. 6; ‘An Ardent Anti-vaccinator’, Peterborough Standard, 4th October 1884, p. 7 ↩︎

- William Tebb, ‘The recent vaccination prosecution’, Peterborough Standard, 18th October 1884, p. 8 ↩︎

- ‘Anti-vaccination’, Peterborough Standard, 22nd November 1884, p. 7. For more information about one of the police officers involved, see Karen Meadows, ‘Sergeant Matthew Lightfoot 1854 – 1914’, Waterfurlong Orchard Gardens, 2018, https://web.archive.org/web/20241109003522/https://www.waterfurlonggardens.com/sergt-matthew-lightfoot. She has also covered the story of the harmonium: Karen Meadows, ‘This Day in… 1885’, The Plot Thickens, 2019, https://web.archive.org/web/20210517165837/https://www.waterfurlonggardens.com/single-post/2019/01/21/this-day-in-1885 ↩︎

- ‘The Alleged Illegal Removal of a Harmonium’, Peterborough Standard, 27th December 1884, p. 7 ↩︎

- Stamford Mercury, 16th January 1885, p. 4 ↩︎

- ‘Stamford County Court, Jan. 21’, Stamford Mercury, 23rd January 1885, p. 6 ↩︎

- ‘Municipal Elections’, Stamford Mercury, 4th November 1892, p. 7 ↩︎

- ‘Stamford Institution’, Stamford Mercury, 24th September 1909, p. 4 ↩︎

- ‘Death of Mr. Cade’, Stamford Mercury, 24th September 1909, p. 4 ↩︎

- ‘New Councillor’, Stamford Mercury, 15th October 1909, p. 4 ↩︎

- Durbach, p. 176 ↩︎

Leave a comment