Feature image credit: Hermann Gattiker – Crossroads on a Road (Fichter Kunsthandel)

This story was originally published in the Peterborough Local History Society magazine (Volume 64, April 2025).

Content warning: Suicide, graphic content.

According to an apocryphal quote from William Gladstone, ‘Show me the manner in which a nation or a community cares for its dead and I will measure with mathematical exactness the tender sympathies of its people.’ Nowhere is this more evident than in the way we have historically treated suicides.

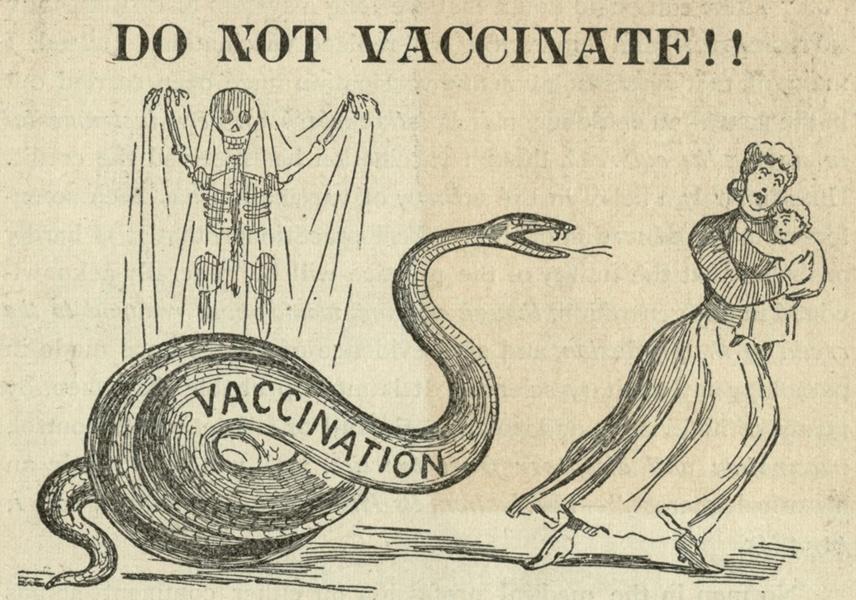

In England, there was a long tradition of burying both murderers and suicides at crossroads, the two being viewed as morally equivalent. A stake was often put through the heart, and sometimes a heavy stone was placed on the face. The origins of these traditions are lost to time, but they are thought to be ways to prevent the spirits from returning, the crossroads confusing the dead so they could not find their former homes. These burials occurred on public highways and at parish boundaries as a way of casting these people out of their communities.1

These beliefs were backed up by the power of law. It was illegal for suicides to be buried on consecrated ground up until 1823. This changed after Viscount Castlereagh, the Foreign Secretary, killed himself in 1822 but was buried at Westminster Abbey. Even then, these burials were only allowed to take place at night until the law was changed in 1882. Suicide remained a criminal offence until 1961.2

Andrew Percival, SSc, of the Peterborough Archaeological Society, related a story of crossroads burial in Notes on Old Peterborough:

‘Crossing the fields now laid out by the great roads of the Land Company, and which at that time were the most secluded fields around Peterborough, and going down Crawthorne Lane you came to a junction—a little lane at the back of Boroughbury, now a wide street behind St. Mark’s Villas, which runs up to Park Road, and there four roads met, where there was a little tombstone which was known as the “Girl’s Grave.” A girl was buried there, with a stake through her body, without Christian burial. The place was very well known, and for long remained in the midst of a potato garden belonging to one of the cottages there.’3

The area had changed a lot by the time the book was published in 1905, most of the houses being built in the 1870s and 1880s. Crawthorne Lane would become Lincoln Road East, which in turn became Burghley Road. At some point, part of the road was also called Allen’s Lane. St. Mark’s Villas, built in Percival’s time, still sit opposite St. Mark’s Church on Lincoln Road today. The medieval Tithe Barn at Boroughbury was demolished in 1890.

Percival’s book was a collection of articles that had already appeared in the Peterborough Advertiser. As early as 1883, he had given a talk where he mentioned the Girl’s Grave. The subject of the talk was ‘Our City, or Peterborough fifty years ago and now,’ so we can surmise that the gravestone was there in the 1830s.4

In 1899, a nonagenarian by the name of Thomas Holdich shared some of his memories with the Peterborough Advertiser. His story includes several additional details:

‘BARBAROUS TREATMENT OF A GIRL’S DEAD BODY

‘Mr. Holdich remembers a girl’s grave in Lincoln-Road-East, where another road crossed, somewhere near where Park-Road crosses Lincoln-Road-East. He had often seen it, and was told that a girl had been buried there under sad circumstances. The girl had taken poison and the verdict at the inquest was one of “Self Murder.” Consequently, the body was carried to this spot—where roads crossed—and at midnight, by the light of torches, it was buried a stake being driven through the body. A stone marked the spot for many years.’5

Holdich can be forgiven for not remembering the official term coroners used for suicide, which was felo de se, literally a felony against oneself.

Another account of the grave was published in the Peterborough Advertiser in 1901, this time suggesting that the gravestone could have still been present up to twenty years earlier and calling the deceased a servant girl:

‘When the street was called Allen’s Lane, it was narrow and crooked, and at one corner there was an ugly and fearsome stone, marking what was popularly known as the Girl’s Grave. A poor servant girl had committed suicide, the jury had brought in a verdict of felo-de-se, and she was buried by the road-side at midnight with a stake driven through her body. It is more than twenty years since I saw the stone which marked the spot. It has disappeared, but the girl’s grave is still there, and there is little doubt that some portion of the body, if not the stake, may not yet have crumbled to dust. Gentleness does not seem to have been a prominent trait in the characters of some of our forefathers.’6

Searching the records, I found someone whose story matches every detail given so far. The Stamford Mercury reported the following in 1811:

‘On Wednesday week died at Peterborough, in consequence of a quantity of arsenic which she had taken in the morning, Elizabeth James, aged 22. As soon as the unfortunate girl began to feel the dire effects of the poison, she disclosed the dreadful secret, and though the best medical aid was called in, the corrosive sublimate baffled every effort, and she expired within twelve hours afterwards.—The Rev. J.S. Pratt, the Vicar, attended her at intervals during the day, and was with her at the moment of her dissolution. He evinced the greatest possible humanity towards her and pity for her melancholy situation. To him she declared, with a mind perfectly collected, that a disappointment in marriage had induced her to destroy herself.—The following morning an inquest was taken before John Atkinson, gent. coroner, when the jury, after a minute investigation, returned a verdict of felo de se. The next afternoon her remains were conveyed to the place fixed upon for her interment, (a short distance from Boroughbury Barns, upon the road from Peterborough to Spalding,) attended by six of her female relatives dressed in white, and a vast concourse of people who had collected together to witness the sad and novel scene.’7

Elizabeth James would seem to be the person referred to in all these stories. Park Road led in the direction of Spalding. The Boroughbury Barns were just a few minutes away on foot.

A later reference in the Stamford Mercury leaves little room for doubt that we have found our person:

‘We mentioned a short time since the death of Elizabeth James, of Peterborough, who poisoned herself, and whose body was buried in the road leading to Spalding. We hear the relatives of the unfortunate girl have recently placed a stone near where her remains are interred, bearing the following inscription:—

Near this spot

were deposited, on the 24th May, 1811,

the sad remains of

ELIZABETH JAMES,

an awful memento against the horrid crime of

SUICIDE.

Passenger take warning;

you see here a fatal instance of

human weakness, and the dreadful consequence

of misplaced affection.’8

Elizabeth was one of at least five people who took their own lives within a three-month period that year.9

The identity of Elizabeth’s suitor and the nature of their relationship will likely remain mysteries. Additional details about her life are hard to find, but a 1955 letter to the Peterborough Standard narrows down her profession as barmaid. Unfortunately, it also paints an ugly picture of the scene at her burial. Far from coming to mourn her passing, many came to relish the spectacle and jeer at the deceased. Elizabeth did not feel what happened to her body after death, but she must have had some idea of the indignity it would experience:

‘As to the burial of a supposed murderer at the east end of Lincoln-road East — it was not a murderer, but a suicide. Early in the 19th century a barmaid at The Bell and Oak who had poisoned herself was buried there.

‘My grandfather when a boy witnessed the last gruesome sight recorded in Peterborough. The rabble gathered with scoff and scorn, a stake pinned down the body, and ‘neath the torches red blaze, the traditional time of interment was midnight.’10

The following year, Rev. J.S. Pratt, the vicar who attended to Elizabeth in her final moments, and John Atkinson, her coroner, acted as witnesses to the dying words of David Thompson Myers at Peterborough Gaol. His public hanging at North Bank, near Fengate, was the last execution in the city. His crime was homosexuality.

Thankfully, we no longer view suicide as a crime, nor do most of us view it as a moral failing. Instead, we see it as a result of mental health problems and societal pressures. With enough understanding and assistance, people need not resort to ending their own lives.

As chance would have it, just down the street from the site of the crossroads is a set of paintings from local street artist Nathan Murdoch. In 2022, he painted a series of portraits of people who had experienced mental health struggles, including himself. He said he wanted the project to lead to conversations about mental health.11 It goes to show how much things have changed.

Nathan Murdoch’s work is in aid of Cambridgeshire, Peterborough and South Lincolnshire (CPSL) Mind. For a range of services, check their websites: https://www.cpslmind.org.uk/get-help-now/ and https://stopsuicidepledge.org. If you are in need of urgent help, dial 999 to speak to someone without delay. For free and confidential support, you can call the Samaritans at 116 123 or text Shout at 85258.

Special thanks to the people who helped me with this article: June and Vernon Bull, Rev. Michelle Dalliston (St. John the Baptist Church), Catrin Davies, Anjanette Ingram (Northamptonshire Archives), Nathan Murdoch, Hannah Piller (CPSL Mind), and Sue Allison and John Pelling (Coddenham Village History Club).

- Robert Halliday, ‘The Roadside Burial of Suicides: An East Anglian Study’, Folklore, vol. 121, no. 1 (2010), p. 81-90 ↩︎

- See Burial of Suicides Act 1823, Interments (felo de se) Act 1882, and Suicide Act 1961. See also Burial Laws Amendment Act 1880, which allowed funerals to take place in Anglican churchyards regardless of denomination. Aside from Castlereagh’s case, Robert Halliday points to an incident where George IV’s carriage was held up by spectators watching a crossroads burial at the current site of Victoria Station in London: Robert Halliday, ‘Criminal graves and rural crossroads’, British Archaeology, June 1997, p. 6. ↩︎

- Andrew Percival – Notes on Old Peterborough (1905, Peterborough Archaeological Society), p. 31-32 ↩︎

- Stamford Mercury, 13th April 1883, p. 4 ↩︎

- ‘Further reminiscences of Peterborough by Mr. Thomas White Holdich’, Peterborough Advertiser, 8th March 1899, p. 3 ↩︎

- ‘The Peterborough Jackdaw’s Flight’, Peterborough Advertiser, 11th December 1901, p. 5 ↩︎

- Stamford Mercury, 31st May 1811, p. 3 ↩︎

- Stamford Mercury, 6th September 1811, p. 3 ↩︎

- Stamford Mercury, 19th July 1811, p. 3 ↩︎

- Letter from A.O. Davis, Peterborough Standard, 4th November 1955, p. 8 ↩︎

- Adam Barker, ‘Peterborough street artist Nathan Murdoch hopes to start conversations about mental health with latest mural’, Peterborough Telegraph, 21st July 2022, https://www.peterboroughtoday.co.uk/news/people/peterborough-street-artist-nathan-murdoch-hopes-to-start-conversations-about-mental-health-with-latest-mural-3777694 ↩︎

Leave a comment