This article originally appeared in Vector, the official journal of the British Science Fiction Association. I also asked some questions about the Megatron flying saucer restaurant, which will appear separately as bonus content on this website.

Catherynne M. Valente has packed a lot into the first 20 years of her career. Her genre-busting work runs the gamut from alternative history to fairytale fantasy to cosmic horror. In addition to writing 27 novels and novellas, she has multiple collections of short fiction and poetry. She is also the creator of a six-year-old human, but motherhood shows no signs of slowing her down. Space Opera, her 2018 bestseller about an interplanetary Eurovision Song Contest, was shortlisted for Best Novel at the Hugo Awards. Her new novel, Space Oddity, picks up where Space Opera left off and reflects contemporary concerns like pandemics, online misinformation, and the threat of all-out war. https://www.catherynnemvalente.com/

Tony Conn is a writer and filmmaker with an interest in all things strange. He is perhaps the world’s leading expert on the Megatron, a flying saucer-shaped restaurant that used to adorn the Cambridgeshire countryside and now features in Space Oddity. https://tonyconn.com/

TC: Could you tell us about your background and early influences?

CV: My parents met at UCLA and divorced when I was very young. I had two stepparents most of my childhood and went back and forth between Seattle and northern California. My dad was an aspiring filmmaker who went into advertising instead, which is very much a family thing on my father’s side. A lot of them intended to be artists and ended up in the family business. My mother is a retired political science professor. She was in her master’s and PhD programmes through almost every portion of my early life that I can remember. She was working for the mayor of Seattle, getting her degrees in public policy, doing advocacy work, and she’s a pretty hardcore statistician as well.

They were in their early twenties when they had me. They had no sense of what was appropriate for a child. I had no boundaries as to what I could read, or watch, or anything. I just had to be vocal about when it was too much for me, which is kind of a modern parenting idea. My mother read Plato’s Republic to me as a bedtime story, specifically The Myth of Er, which is this allegory about what happens when we die. At five, she had me read The Breasts of Tiresias by Apollinaire. It’s above the pay grade of adults, let alone a small child. My mother had no sense of that. In my mom’s house, there are stacks of books that are now end tables. Cairns of books everywhere.

Both of my birthparents are big musical theatre people, so I grew up seeing musicals all the time. I’ve always had this really low voice, since I was ten. I wanted to be a singer, but there weren’t any parts for somebody with a voice like mine. My mom also has a master’s degree in drama, so I remember when Beaumarchais was a big thing in our house. At eleven, all that anybody talked about was The Barber of Seville.

I had a lot of influences from my parents. My mom read every murder mystery. My dad is hardcore science fiction. And then, my stepmother Kim is the world’s biggest Stephen King fan. Horror was my first love, both as a reader and a writer.

TC: Is it a coincidence you ended up living in Maine?

CV: I would like to pretend I did not move to Maine because I got obsessed with Stephen King as a small child, but that would be a lie. I read Stephen King by the time I was nine. I found Salem’s Lot in the garage and sat down on the floor to read it. I was obsessed with Maine as a child. To me, it seemed like that’s where they kept the magic. In all the books I read, the magic is in Britain, or Europe, but in Stephen King there was this place in America where horrible but magical things could happen. Recently, I was invited to contribute to an anthology of new stories set in the world of The Stand called The End of the World as We Know It, so I got to write in Stephen King’s universe as a grown-up.

TC: You’ve mentioned elsewhere that you have ADHD. Does that go some way to explaining how prolific you are, and the way you jump between genres and styles?

CV: Yeah. I really can’t do the same thing twice in a row. It nearly kills me. Part of my brain is desperately trying to wander off and find something new to do, so I do jump genres a lot. Maybe I would’ve had a more successful career if I had stuck to one thing, but I just can’t do that. The thing that I enjoy the most is writing something unexpected, that people think I would never write. I’m always looking for that thing that kicks off my imagination, that hyperfocus.

Honestly, it’s not good for me to take a long time to write a book. The best way to do it is to have between eight and twelve weeks, and produce an entire manuscript in that time, all the research having been done. I can believe in myself and the project and everything else for about that amount of time before it all crumbles and falls apart. I didn’t know I had ADHD till I already had several books out, but I do think The Orphan’s Tales (2006), which was my first big New York book, I should have been able to give to a doctor and receive a prescription.

TC: One strand that runs through your work is remix culture – turning genres on their heads, taking new perspectives in stories that might seem familiar. Do you think that reflects the times we live in?

CV: Yeah. We’re pretty far past postmodernism. We screwed up by calling it postmodernism, and now nobody knows what to say next about that kind of thing. I remember, in creative writing classes in college, being told to not use modern pop culture references because it dates your work. I think that, for science fiction people, it’s just not the same. Using modern cultural references in order to introduce something totally alien as a culture is really helpful, and we would be loath to give it up. I think a lot of that has changed with things like Don DeLillo’s White Noise, which I’m not a huge fan of, but it’s impossible to argue it’s not totally seminal. I think it certainly changed with the advent of the internet. We’re constantly making memetic references to the point where we sound like that Star Trek episode with Darmok and Jalad. The progress of memetic culture is fascinating.

TC: Were you surprised by how successful Space Opera was?

CV: I think we all were. It was supposed to be a novella, for one thing. We all thought it was going to be pretty niche. No Americans knew what Eurovision was at the time. Thank you, Will Ferrell, for that movie (Eurovision Song Contest: The Story of Fire Saga). I no longer have to give a short TED talk on what Eurovision is before I give a reading. The idea of an American writing a comedy about Eurovision for Americans, which would appeal to neither Americans nor Europeans, who don’t want to hear an American’s opinions on Eurovision – none of us really thought it was going to be a big hit.

Then, that first print run sold out weeks before the book came out. We went through something like nine editions in the first six weeks because we just couldn’t keep it in stock. Popular Mechanics had it on their Father’s Day gift guide, so it was: whiskey, knives, boots, book with a disco ball and girl whose name is spelled funny on it. Just wildly strange. Almost no publicity was done for it. It was all word of mouth. We were all very shocked, and it sold movie rights right away. Unfortunately, Covid killed that project, but it is under development as an animated series right now.

TC: I was going to ask about that…

CV: Yeah, so Universal picked it up almost immediately, less than a month after the book came out. There was a whole team. We had songwriters. It was a going thing, and then, you know, Covid killed a lot of things. Everybody involved still wants to do it, but it just wasn’t meant to be. Never before have I had an option expire and attached to that email was the next option offer, because they’d been waiting for it to expire.

I think, in retrospect, that an animated series is a better destiny for it. It doesn’t cost nearly as much to animate all those aliens as it does to CG them, and I think that you can do a lot more with the structure of an animated series than you can with a two-hour feature film. For the same kind of reason, it’s always been so difficult to adapt Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. The nub of Hitchhiker’s Guide, and it’s true of Space Opera as well, is those expository comedy bits explaining some little aspect of the world. That’s most of what people remember, not necessarily the plot.

Lower Decks has been great at doing good science fiction while still being comedy. I think we have a lot of examples of how to do more elevated animated series these days than back when I was a kid, and it was The Simpsons or nothing.

TC: Space Opera and Space Oddity contain a lot of British references, like Douglas Adams, Doctor Who, Monty Python, David Bowie. Would you describe yourself as an Anglophile?

CV: I think it’s a complicated thing. We are taught so much British culture in America, to the point that it can feel like American literature, even in our own colleges, is a secondary concern. Britain, and British culture, has been excellent at spreading and taking root all over the place, for good and for ill. I guess I’m an Anglophile, but when you grow up on fairy tales and King Arthur, you end up having this idea about the UK.

I went to university in Edinburgh, and that’s part of why the band in Space Opera and Space Oddity is British. At the time, I thought it would be funny because of the UK’s traditional placement in Eurovision. Then, of course, a few years after the book came out, it’s hosted in Liverpool with a song called Space Man, because of course.

And good Lord, who doesn’t love Douglas Adams? I wouldn’t want to meet that person. When I wrote the first chapters of Space Opera, I wrote it very quickly, and I was really happy with it. I’d never done anything that was first and foremost a comedy. But I had to sit back and say, “Alright, so you have Brits in space, and you’re writing it like this. You’re going to get compared to Douglas Adams. Are you comfortable with that? Are you cool with hearing how you didn’t live up to Douglas Adams?” I decided that I was okay with that, and to some extent it took some pressure off. Was I going to sit down to write the great science fiction comedy novel? Absolutely not. I could shoot for the bronze, and it would be fine.

There are several references to Douglas Adams throughout both books. He’s a brilliant and unsurpassable talent, and I adore his work. Terry Pratchett as well. All of the things that you mentioned. To be allowed to hang out outside the house where they all once lived is fine for me. I can hang out in the garden.

TC: Did you have to do a lot of research into British slang and regional dialects?

CV: Not really, because I did live there. I think I made it harder for myself, because there are things that bother me when Americans write British characters. I didn’t want to overuse “bloody.” I didn’t want to use “Oi, guvnor!” I didn’t want to do any of that stuff. I gave myself three “bloody”s per book and had to be a little bit more creative with my intensifiers.

TC: I believe all the members of the band are of mixed heritage…

CV: They are, which is important to me, and very deliberate.

TC: Did that involve a lot of research, into British-Asian culture, for example?

CV: Yeah, that did involve more research. That was more for the first book, because those characters are defined by the second. Richard Ayoade has the same kind of cultural background that Decibel Jones has, so I listened to a lot of interviews with him. There’s a lot of Ayoade’s voice in Dess.

You always want to do the absolute best you can, even in comedy. I’m sure that there are mistakes. There’s always mistakes. But it was important to me to have this plucky, punky band that is made up of Britons who have a heritage that is not just of the British Isles, because that’s such a huge part of Britain’s history and heritage.

TC: You have a playful attitude towards gender and sexuality in the Space Opera books. Was that something you consciously wanted to explore? Do you think science fiction is a good way to do that?

CV: I think it’s a great way to explore that. There is no reason an alien species should conform to our ideas of gender. Much of the animal kingdom doesn’t. Once you get outside mammals, you have all kinds of different combinatory ways of reproducing. I wanted to be honest about how weird aliens should be. My rule was: You must be at least as weird as things we already know about.

Within the alien species, I wanted to have a huge variety of gender expression, and then rock stars have always been a little bit exempt from the kind of judgement that us normal people get. Freddie Mercury and David Bowie were totally acceptable to play in straight, regular households, and they were wildly nonconforming. I wanted to have a lot of fun with that. I’m queer myself and I felt like, particularly in this day and age, if you’re going to do Brits in Space, there’s no reason not to push it a little further, make it a little gayer and younger and stranger, particularly because two of the genres of cultural expression that often get exempt from prohibitions against your own expression are comedy and music.

The other way that the species’ anatomy came about is reverse-engineering it from the kind of music that I wanted them to represent. Music has a lot to do with our anatomy. The beats that feel natural to us. Our own heartbeat, that’s the beat that we have in our bodies all the time. We have ten fingers. It determines the kinds of instruments that we play. If we had twelve, we’d be playing different kinds of instruments. The resonance chamber created by our inner ear and skull determines the range of sound that we enjoy and don’t enjoy. If you have a completely different anatomy, it would be a completely different kind of music.

TC: Is there an overarching narrative to the series?

CV: I very rarely have an overarching plan. It’s that ADHD again. I want to keep myself surprised constantly. I try not to plan prescriptively too much, because then my brain thinks it’s already done this book and will go on permanent hiatus.

TC: You said you hate to do the same thing twice. Did you feel under pressure to recreate the first Space Opera book in Space Oddity?

CV: Sure, a little bit. I knew when I finished writing Space Opera that I would probably want to go back to that world. The first one doesn’t end on a cliffhanger, but there’s obvious threads to another story there. I didn’t really want to commit to it until I had an idea for what book was going to be. It was about a year before we sold the sequel, and then it was like, “Well, can I get back into that voice?” I ended up folding it into the sequel, that anxiety about your difficult second album, and what happens to the Hero’s Journey when you’re done with it.

When I first started writing it, Covid had happened. I had Covid in February 2021, when I was finishing the book. We are very fortunate it’s in English and paragraphs because I was completely delirious. I went and quarantined at a friend’s house for eight days and, even in my feverish brain, I thought, “I will never again have eight days to myself, so if I’m going to finish this book, I have to do it now.”

Because Eurovision was cancelled, it seemed to me that’s what the book had to be about on some level. But by the time that I was editing it, Russia had invaded Ukraine and then removed themselves from Eurovision, and I felt like what the book was about had to change a little bit too.

TC: Did it feel cathartic to write this satire of what was going on at the time?

CV: Yeah. Covid was really rough for writers. You need to experience things. It’s a real part of the process, at least for me, and to suddenly have no input but your own four walls made it so strange. I live on a little island in Maine. I couldn’t even get food delivery. We have one store that everyone goes to and one boat that you have to take to get to the mainland. People lost their minds. It was really hard to make something that’s new and exciting when nothing was new and exciting.

TC: You wrote a touching dedication to Christopher Priest in the new book. You also lost a lot of family members while writing it. Can you tell us how that affected you?

CV: Between the start of lockdown and the end of 2021, my husband and I lost 13 family members. It was gruelling. There were times when it was just month by month. My husband’s grandmother died during my grandfather’s funeral. It’s hard to write comedy when everyone around you is suffering. I think the books that I wrote during this time, Osmo Unknown and the Eightpenny Woods (2022), which is literally a book about death, and Space Oddity, are lobbed into the future to explain what we were all going through. It’s weird when your own life starts to fall apart at the same time the world is falling apart, because you can’t tell which of that is your problem and which of that is that everything’s messed up.

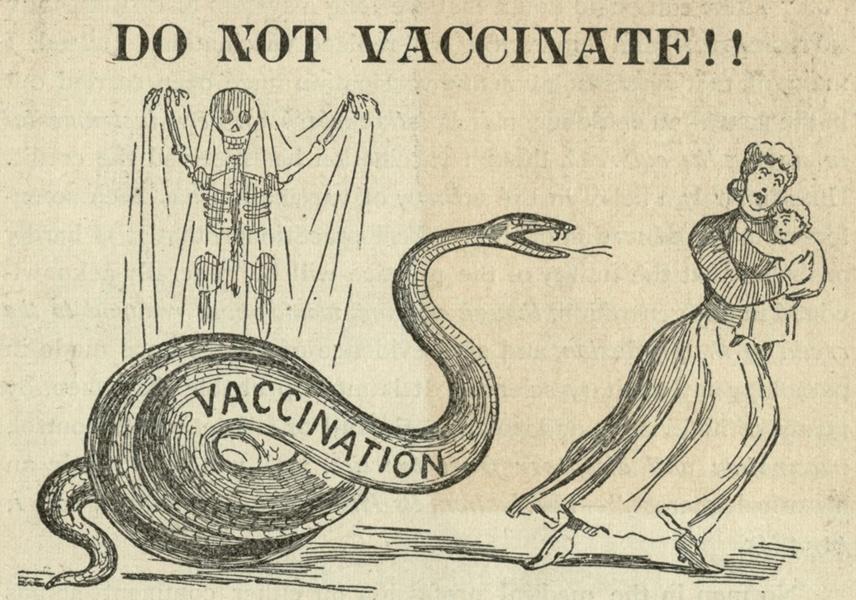

The world has gone absolutely spare in the last several years. I don’t like people pretending that it’s not unprecedented. It is. None of us experienced a pandemic before. That’s new for all of us, and no-one’s getting therapy about it. I think Space Oddity is partly me working through it. It takes time to make art out of trauma, because the trauma has to stop before you can make art. There has to be a minute where you’re not being actively traumatised to process all of that into art. I think we will see everybody’s Covid novels over the course of the next 10 or 15 years, as people have different speeds of processing and writing.

TC: Does having a child mean that you see literature through a new lens?

CV: In some ways. The thing that is bringing me a lot of joy right now, as my kid’s just turned six, is sharing some of the more complex young reader books that I loved as a kid, between The Hobbit and The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe. There’s this book called Seaward, by Susan Cooper, that most people have never heard of, but it was absolutely my favourite when I was little. A lot of the fiction that I’ve been taking in is rediscovering those things that I loved so much as a young reader.

In Space Oddity, there’s the whole bit in the beginning about the Blowout, which is what happens to first contact cultures when they finally get a chance to process what they’ve gone through, and they all lose their minds. The comparison is to a baby’s blowout diaper. It’s obviously right from my kid. Also, for a long time, I couldn’t read or watch anything where bad things happened to children. I just couldn’t handle it. I’m starting to get over that now, but I still am a lot more squeamish about that than I used to be. It does change your perspective somewhat.

I still think of this child as like a rogue AI that I’m slowly programming. You will tell them something and they will take it completely literally. When they were a little younger, we said, “This is your body. It belongs to you. Nobody can do anything to your body that you don’t consent to.” So, I get a phone call from daycare because my son has pushed a little girl off a chair into the gravel, and nobody knows why it happened. The minute we walk away, the three-year-old tells me, “Brooklyn would not stop singing Let It Go into my ear, and my ear is part of my body, and I get to say what happens to my body, and nobody can do anything to my body that I don’t consent to.” I’m like, “Okay, well, thank you for listening to that lesson. You still can’t push somebody. That means you’re doing something to her body.” It’s the most perfect example of how a robot would interpret that instruction. How I think about AI and how people learn things has certainly changed a lot, watching this ball of id slowly grow a superego.

TC: Do you have any other projects that people should look out for?

CV: Space Oddity is the big thing. I’m coming up on finishing a new novel for Tor called Nobody But Us. I have a number of short stories coming out in quick succession in 2025, including the Stephen King anthology, The End of the World as We Know It. I have stories coming out in Uncanny and an anthology called The Book of the Dead.

Space Oddity is released on 9th January 2025 in the UK.

Leave a comment